Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Are rail operators responsible for preventing train suicides?

Published: Thu, 2015-04-23 12:00- Likes 3

Although less common than people think, it's always shocking when someone commits "suicide by train." Do these suicides have predictable patterns? Who should be responsible for preventing them? Can they be prevented?

Jan Botha, PhD, has completed extensive research on this topic for the Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI). His reports include Suicides on Commuter Rail in California: Possible Patterns-A Case Study (2010) and more recently, An Approach for Actions to Prevent Suicides on Commuter and Metro Rail Systems in the United States (2014).

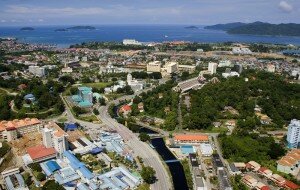

"Some patterns do exist," said Dr. Botha. "In one case study, we found that about 20% of rail suicides occurred at stations, two-thirds within one-half mile from stations and two-thirds within 0.3 miles of road crossings. They occur primarily during times of high train traffic and in areas where population is dense. But the expected 'hot spots' were not found in the two studies conducted – for instance, near mental hospitals or similar sites."

Dr. Botha's research in the 2010 study found little correlation between suicides and time of year, although September saw the fewest occurrences. Most suicides occurred on Mondays or Fridays, especially during times of peak rail traffic. And males were 3.5 times more likely than females to use rail suicide.

Recently in Northern California, there was a cluster of suicides by students from the same high school. Some people placed the blame on school pressures, though it's unknown if there was a common cause. It's also true that "copycat" events may take place because one person's suicide may propel another one to take that step. Care should therefore be taken in the publicity of these events.

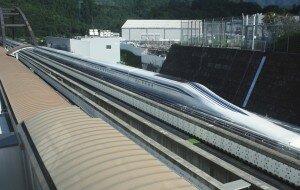

"Statistics showed that in 2010, there were 38,364 suicides in this country, but there were only about an average of 30 suicides per year reported during the period 2003-2008 on 48 rail systems operated by transit agencies. It's their spectacular nature that elevates them to a higher profile. What often follows is pressure on the rail operators to take steps to prevent these events. But what can they do that remains within reasonable effort and expense? How much responsibility is theirs?"

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that the average cost of a suicide in the US was about $1 million based on 2005 data. The MTI research noted that the cost of a rail suicide could be much higher because it may include travel delays on the rail system and the effects on the surrounding road and public transportation systems, as well as the costs of restoring the rail system to full operation. The costs associated with the impacts on engineers and train crews, including personnel turnover, are also part of the latter cost.

"Realistically, suicide prevention is a community responsibility," said Dr. Botha. "Rail operators certainly can do their part to prevent suicides on tracks, stations, and other property. But ultimately, this is a public health issue. The principal focus of the rail authorities should be on safeguarding the effective functioning of the rail transportation system and to prevent suicides from impeding this function."

Many operators have invested in signs promoting suicide hotlines, surveillance systems, expensive barriers, or rail system personnel who watch for suspicious behavior. While the cost of some of these actions cannot be justified based solely on suicide prevention, some systems can "piggyback" on others, implemented for other reasons, to make these projects economically feasible. These actions can be targeted at the places where most suicides could occur.